Produced by Judy Rybak

[This story first aired on Feb. 4. It was updated on Dec. 9.]

HAMMOND, Ind. — For nearly two decades, Sally Glenn went to prison every other weekend to visit her son, Roosevelt.

“It would hurt me. And when we’d leave there I would cry,” she told “48 Hours” correspondent Maureen Maher.

Roosevelt Glenn’s daughter, Darniese, who was just 7 when her father went to prison, was often by her grandmother’s side on those visits.

“I was nervous for him due to the fact I knew he was a very innocent man behind bars with very bad criminals,” she said.”I had suicide all over me … for a while,” Roosevelt Glenn said in tears.

“And what stopped you?” Maher asked.

“I believe it was the power of God,” Glenn said. “I was a good man before I went to prison, but I wasn’t a man of faith. Prison changed my way of thinking and it made me a man of faith.”

Darryl Pinkins was also in prison.

“How do you survive in that environment?” Maher asked Pinkins.

“You have to become … colder, as far as emotions,” he said, “because I don’t trust people like I used to.”

“I don’t know if they realize you’ve pretty much taken the most valuable thing people have… time,” Pinkins’ son, Dameon, said. “I feel like I’ve lost the most important time of my life, where — a son bonds with his father and becomes a man.”

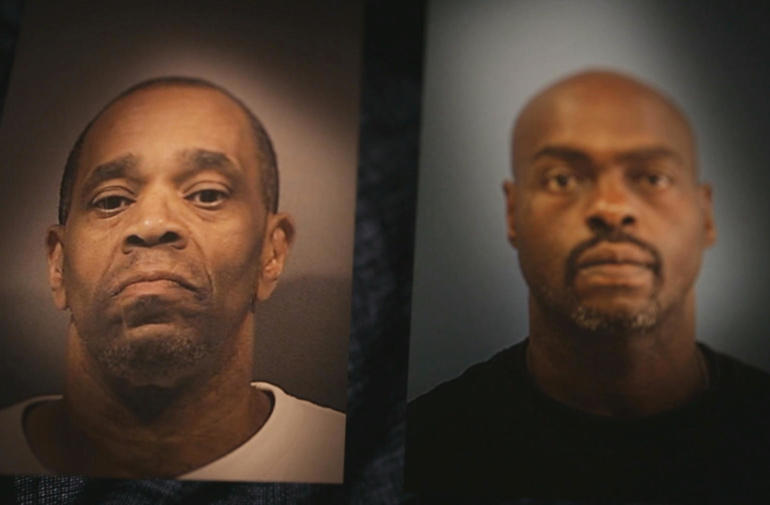

Darryl Pinkins and Roosevelt Glenn

CBS News

Mildred Pinkins lost her eldest son.

“I just couldn’t imagine him bein’ locked up,” she told Maher. “My child. He’d never been in trouble before. Why now?”

The trouble started nearly three decades ago, when Detective Lieutenant Mike Solan, now retired, worked so diligently to solve a brutal rape case in Hammond.

“I’ve got one job as a detective, to get to the truth,” said Solan.

“I want you to understand something, Maureen,” Solan told Maher. “When you do a criminal investigation … you watch where the evidence takes you, and you follow it.”

“This was tunnel vision police work and they let the real bad guys go,” said Fran Watson.

Watson, an Indiana University law professor, runs the university’s wrongful conviction clinic, where every semester, law students — like Max, Polly and Brenda — eagerly sign up to help Watson investigate cases.

“Did it change your opinion about the law or the system?” Maher asked the students.

“I guess I started my career knowing that the system can fail,” said Max.

For the last 15 years, Professor Watson has enlisted hundreds of her students to help her battle Detective Solan, and the entire judicial system, to overturn the convictions of Roosevelt Glenn and Darryl Pinkins.

“You start … looking at the case … thinking … ‘Fran cannot possibly be right about this.’ I mean, these people got convicted for a reason,” said Polly.

Professor Fran Watson, right, and law students

CBS News

“I dreamt of a professor and law students comin’ to my rescue,” Glenn said. “I used to see it on TV all the time.”

“…then one day I said … ‘I got my dream team,'” he told Maher.

Their first assignment: study the case file — the scientific evidence, a victim ID, the political pressure to solve the case quickly, and accusations of racism.

“… all of a sudden, each of us had our own ‘aha’ moments,” Polly told Maher.

It was about 1 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1989, and the first of two bump and robs that would occur that night was about to take place.

“And what that means is you’re a single woman driving alone at night, your car gets bumped,” Watson explained. “…and they would grab you … rob you and … sexually assault you.”

Flight attendant Jill Martin was on her way home on Interstate 65, not far from Hammond, when her car was bumped from behind.

“A car occupied by at least three black males. … She pulls over. And the car pulls in front of her,” Solan told Maher. “And then a man comes out of the driver’s side of that car, and calmly … walks to her car. …And the black man says, ‘Are you all right, ma’am?'”

“Fortunately for her, a pickup truck was coming down the highway, and started to pull behind them thinking it was an accident,” Solan said. “All three blacks walked rapidly to that car, got in, and left.”

Jill Martin said the men took off. Still, she was able to get a look at their car and write down a partial license plate number. About 30 minutes later, there was another bump and rob. The victim in this case, who we will call “Jane,” was also on her way home.

“Jane,” 26, was stopped at a traffic light just one block from her home and husband when she was bumped from behind.

“So she got out of the car, and she walked to the back of her car … and a black man … gets out of the car, and walks very calmly, very leisurely to her, and says, ‘Are you all right, ma’am?'” Solan told Maher.

They were the exact same words flight attendant Jill Martin reported hearing less than an hour earlier. But this time there was no escape.

“Before she has a chance to respond, he grabs her by the arm,” Solan continued.

“Jane” says it all happened so fast. Two other men appeared, grabbed her from behind and forced her into their car. Then, both cars sped off. Jane would later report that she was stripped naked, and all five men took turns brutally assaulting her in the backseat of their car.

“She gave a very detailed statement to Lieutenant Solan,” said former Lake County Prosecutor Joe Curosh.

“It’s her testimony that all five men ejaculated,” Maher noted to Curosh.

“Uh-huh,” he affirmed.

“Jane” told police that these coveralls — also known as greens — were used to cover her face while the assailants attacked her.

Fran Watson

Solan had the rapist’s semen — giving him their DNA. But the national DNA database did not exist yet, so he still had to find the attackers. Solan did have the workman’s coveralls, also called “greens.” “Jane’s” attackers had used them to cover her eyes. She was still clutching them when she was forced back into her own car and released.

“Westex lot number 311 was stamped into the greens,” Solan said. “There was a tag there sayin’ size medium.”

Solan tracked every pair of medium coveralls stamped “Westex lot number 311” until he got to a scrap metal management company called Luria Brothers.

“And I … took the greens out of the bag, and I held them up, OK. Kevin Barker who takes care of greens says, ‘If those are our greens, I know who we gave them to,'” said Solan.

Roosevelt Glenn was an employee at Luria brothers who wore size medium greens. Four days after the attack, Glenn reported his coveralls had been stolen on the night in question. Two more employees had also submitted and signed reports stating that their coveralls were stolen that night as well: Darryl Pinkins and a man named Bill Durden.

“…because they signed those sheets, they attached to each other that … the night of the rape they were together when they left Luria Brothers,” said Solan.

That’s not all Solan tracked to Luria brothers. Based on descriptions given by both women, Solan determined that the car the attackers were driving that night was a 1970s green Pontiac Catalina. So, he tracked down every single registered car in the area that fit that description.

“Fortunately there were only nine in the Lake and Porter counties registered cars of that nature, seven belonging to white people, two belonging to black people,” Solan told Maher.

One of those two cars belonged to Gary Daniels, a janitor at Luria Brothers.

Solan now believed he had a fourth rape suspect. There was just one problem; remember, Jill Martin had given police a partial license plate number.

“Did the plate match on Gary Daniels car?” Maher asked Solan.

“No,” he replied.

But the plates did match a car that had been stolen the night before the attack. Solan contends the men stole that car, sold it for scrap metal and put the stolen plates on Daniels’ car.

“It doesn’t make sense why they would steal an entire car, and then put a plate on somebody else’s car,” Maher noted to Solan.

“Yes,” he replied.

“Why not … just use … the stolen vehicle?” Maher asked.

“I can’t … question, other than the fact that they stole a car,” said Solan.

But the fact is these men were never charged with stealing any car. And no DNA was ever found in Daniels’ car linking it to the crime.

Solan still needed one more suspect. “Jane” said five men attacked her, so Solan went back to Luria Brothers and found a fifth suspect, Barry Jackson.

“What did you have on Jackson?” Maher asked Solan.

“Jackson, everybody said … he’s out with them all hours of the night. And that was enough for the judge to say, ‘OK.'”

Solan easily got an arrest warrant for all five men.

“I remember him comin’ to my house … Knocking on my door and asking … me, ‘Why don’t you tell your son to plead guilty?’ I said, ‘Oh no, Darryl is not guilty of nothin’. And I slammed the door in his face. And I told him, ‘Don’t come to my house anymore,'” said Mildred Pinkins.

AN EXPLANATION FOR THE COVERALLS

“I didn’t do it. I couldn’t do it. I wouldn’t do it,” said Roosevelt Glenn.

“And, when you heard the word, ‘rape?’ Maher asked.

“It sent chills through me. I couldn’t believe that my name was bein’ associated with such a crime,” Glenn replied.

Roosevelt Glenn, who, like Darryl Pinkins, had never been in trouble with the law, will never forget the day he was arrested and charged with a monstrous crime.

“I didn’t do it. I couldn’t do it. I wouldn’t do it,” said Roosevelt Glenn.

CBS News

“It was a little hard because I know the picture they was paintin’ of me was — furthest from the truth. I mean, it was like a night-and-day situation,” Glenn told Maher.

“I’m a rape advocate. And I knew that he didn’t fit all those characteristics like that,” said Renitta Stout, Glenn’s sister.

“Me and my sister probably as close as two siblings could possibly be,” said Glenn.

(L-R) Loreen Glenn, Renitta Stout, and Sally Glenn. Stout, center, made it her mission to fight for justice for her brother.

CBS News

Stout says because of her work with rape victims, she knew the Hammond Police Department, she knew Detective Solan, and she knew her brother was no rapist.

“So, it was that night that we started fighting for him,” said Stout.

“And you’re still fighting to clear his name?” Maher asked.

“Yes, and I won’t stop,” said Stout.

“My aunty Renitta … you could see that she was tired, but she would never … give up,” Darniese Glenn said. “…she would go stand in front of the City Hall … to get her brother out, ’cause she knew he was innocent.”

“Roosevelt doesn’t deny that those were likely his coveralls,” Maher noted to Professor Watson.

“I don’t think he can deny those are likely his coveralls,” she replied.

Glenn says there is an explanation. Nearly two hours before the brutal gang rape, he was at Luria Brothers with coworkers Darryl Pinkins and Bill Durden. It was 11 p.m. and their shifts had just ended. The men say that they all got into Durden’s car with a plan to stop at the local liquor store to cash their checks, grab a beer and go home.

“But before we can get there, his car start havin’ problems,” Glenn told Maher. “…and he said, ‘It’s my oil. I don’t have any oil in the car.’ It was runnin’ hot. So we left there, the three of us walkin’.”

“They exit Durden’s car and they walk away. And there’s … a state police trooper,” Watson explained. “…he sees them walking away from that disabled vehicle. So it’s undisputed the car broke down and they walked away from it on a frigid night.”

The men say they took only what they needed and walked to a pay phone. Roosevelt Glenn called a friend who picked them up, and then let Glenn use her car.

“After we dropped her off, we went to … cash our paychecks,” And the lady there, she was very nice. She — you know, she sees us all the time,” Glenn explained. “And so she said, ‘You guys are late.’ … I said, ‘Yeah. The car broke down.'”

From there they bought two quarts of oil and headed back to Bill Durden’s car.

“…and that’s when we found out that the windows had been broken out,” said Glenn.

The car had been broken into. The passenger-side window was shattered. Two shopping bags and a duffel bag, which had been left in plain sight, were gone. Inside those bags: three workman coveralls.

“…he does not dispute that those are his greens. He said, ‘Those are my greens. … They were stolen from the car,'” Maher told Solan.

“That’s the story he gave,” Solan replied.

Solan was so sure he had the right guys that he urged the men to confess. He told Darryl Pinkins DNA was better than a fingerprint.

“…then if we didn’t do the crime, DNA will surely exonerate us,” Pinkins told Maher. “So we told them, ‘Well, bring the test on.'”

But long before the test results were in, there was a stunning turn of events. For nearly five months, the victim, “Jane,” had insisted she could not, would not ID the suspects. She had even refused to participate in any physical or photo lineups. Then, she showed up to the courthouse for a hearing.

“The place was jammed, Maureen. Even people standing — against the wall,” said Solan.

Solan says Darryl Pinkins — out on bail and wearing street clothes — walked into the packed courtroom through the front door. The moment “Jane” saw him, she reportedly recognized Pinkins as the rapist who first approached her car.

“Do you think that the ID was significant in terms of this case?” Maher asked Curosh.

“Oh, yes, I think it was,” he said. “Oh, yes.”

Solan now had “Jane’s” ID of Darryl Pinkins, the coveralls that belonged to Roosevelt Glenn, and a hair found on “Jane’s” clothing. An expert was prepared to testify that it matched the hair on Glenn’s head.

“When they said they had my hair,” Glenn told Maher, “I was like, ‘Run every test you’ve got. It’s not my hair.'”

Detective Solan also obtained DNA evidence from the victim’s sweater.

Fran Watson

The hair had no root, so at the time there was no way to test it for DNA. But the state could test several semen stains found on Jane’s sweater and jacket for DNA. Three months after Jane identified Darryl Pinkins, the results were in.

“… and it’s those … stains that Durden, Pinkins, Glenn, Jackson, Daniels are all excluded from,” Watson said. “Those men did not contribute to those stains.”

Fran Watson says the DNA results did not match any of the five men — Bill Durden, Darryl Pinkins, Roosevelt Glenn, Barry Jackson or Gary Daniels — who were arrested

The test results showed three clear DNA profiles in the mixtures: the victim and two men — neither of which were a match to any of the five men who were arrested.

There was additional male DNA in the mixture, but it was missing unique DNA markers from each of the five of the men, which means, according to DNA expert Greg Hampikian, there is no way any of the five men arrested contributed to the stains.

“It’s like … if the phone number begins with … the number eight and your phone number does not begin with the number eight, you’re excluded,” Hampikian explained. “The DNA did that, in great detail … and everybody knew it before trial.”

But the State disregarded those results, arguing that DNA was so new, the tests were inconclusive. Prosecutors did concede there was not enough evidence against Barry Jackson and Gary Daniels, and dropped the charges against those two men.

“They white their names out. And then … they refile — showing that Daniels and Jackson have been dismissed,” Watson the students.

Far more confident in the case against the remaining three suspects, the state set its sights on convicting Pinkins, Glenn, and Durden.

“How do you take somebody’s life away and act like it was nothing?” Renitta Stout asked.

HOW THE DNA WAS EXPLAINED AWAY

It was Jan. 28, 1991, and the first to go on trial was Bill Durden. The most damning evidence against him: his ties to Pinkins and Glenn on the night of the crime. The result was a hung jury.

“We never retried him,” said Solan.

“And why wasn’t he retried?” Maher asked.

“The weakest case of the three,” Solan replied.

The next to go to trial was Darryl Pinkins. He was convicted on three counts: rape, criminal deviate conduct and robbery.

“When the judge said, ’75 years,’ I’m 38 years old,” Pinkins said, “that’s like a death sentence. I’m a die in prison for a crime I didn’t do.”

CBS News

“My knees kinda like — buckled a little. I moved a little, swerved a little. And I couldn’t believe it. I was like, ‘This don’t make sense,'” Pinkins said of the verdict.

“When the judge said, ’75 years,’ I’m 38 years old,” Pinkins said, “that’s like a death sentence. I’m a die in prison for a crime I didn’t do.”

“And one night I — I hit rock bottom,” he continued. “And I– attempted to take my life.”

“It’s rough. It’s very rough,” son Dameon Pinkins said. “Um, I wouldn’t wish this on anybody. …’Cause … it’s a lot.”

Roosevelt Glenn was tried twice: the first trial ended in a hung jury; a second jury convicted Glenn of rape.

“I was in such shock that I couldn’t even think,” Glenn said. “And then I heard my mother and sister scream.”

“It was a bad day. For everybody,” said Sally Glenn.

“My grandmother would always ask me, ‘Am I ever gonna see my grandchild on this ground again? Because I know he didn’t do it,'” Renitta Stout told Maher in tears.

Hope dwindled in this case for about a decade. Then, along came Professor Fran Watson’s wrongful conviction clinic, and her law students.

“Did you walk in thinking, ‘Well, they convicted, then they must have had something,'” Maher asked the students.

“I think that’s what we all hoped,” Polly replied. “…we were all … in our third year of law school. That’s what we’d been taught.”

“Having gone through all the evidence … there’s nothing to me that, outside of the coveralls that really indicates that they’re guilty,” said Max.

But the real problem for the defense has always been the victim’s ID of Darryl Pinkins.

“That ID is deeply flawed,” Max said. “I would say that ID should have been problematic from day one.”

Problematic, they say, because it contradicts the victim’s initial statement given to police.

“I thought she said they were young, punk-sounding,” Brenda discussed with Watson.

“She said young … black males, in their 20s, punk talk,” Watson affirmed.

Not one of the five men first arrested fit the description of a young punk — especially Darryl Pinkins, who was 37-years-old and married with young children at the time. But even more disturbing to the young investigators, the crime spree continued even after the men were arrested. In the next seven months, there were 18 bump and robs, and one bump and rape.

“So then how could it be you guys if it was still happening?” Maher asked Pinkins.

“Well, the … word they used … was copycat crimes,” he replied.

Ultimately, it was the way the prosecution handled the DNA evidence that deeply troubled Professor Watson and caused her to reach out to DNA expert Greg Hampikian. He believes the prosecution intentionally downplayed the results of the DNA test by using a significantly less reliable test called serology. Basically, the State argued that the men could not be excluded from the semen, because their blood types could be found in the stains.

“Everybody in the room would have been in that stain,” Watson said, reviewing the case with her team, “because everybody in the room’s A, B or O blood.”

“To even use blood typing when you have DNA is — is so unethical as to, you know, make my blood boil,” said Hampikian

And this is where it gets even more complicated. After arguing that the men probably did contribute to the semen stains, the prosecution then contradicted itself, by saying that Pinkins and Glenn may not have ejaculated at all. This according to several jailhouse informants who allegedly reached out to Detective Solan.

“Pinkins … he confided in his cellmate. And he asked the cellmate these questions. ‘Is it rape if you didn’t ejaculate?'” Solan said. “He also tells him, ‘I’m not worried about the DNA evidence because I didn’t ejaculate.'”

That informant got a plea deal in return for his testimony. And so did a snitch who testified that Roosevelt Glenn told him he only kissed the victim. But remember, the victim told police she had been raped by each of the five men, and that all five men ejaculated.

“You’re raped. You’re bein’ hurt,” Solan said. “If you think you’re gonna be accurate on did everyone ejaculate … well, you’re fooling yourself. You’re wrong.”

“How do you as an investigator decide which parts of her eyewitness testimony to use and which parts to discount?” Maher asked.

“I take it all. I don’t discount it unless the evidence discounts it,” Solan replied.

“Do you believe 100 percent that these two men are innocent?” Maher asked Watson’s students.

“Yes, absolutely,” said Max, with Polly and Brenda in agreement.

“The more you read the case, you see … all the factors … leading to wrongful convictions, like jailhouse snitches … ineffective assistance of counsel … junk science,” Max continued.

Karen Freeman-Wilson was a prosecutor-turned-public defender, when she was assigned to represent Roosevelt Glenn in his second trial.

“There was part of me … that just could not believe that they were pursuing this case,” Freeman-Wilson said.

“I talk about this case as the case that has haunted me throughout my career,” she continued. “Because I knew he wasn’t guilty.”

Today, Freeman-Wilson is the mayor of Gary, Indiana.

“I really didn’t know Detective Solan,” the mayor told Maher. “But I was willing to give him the benefit of the doubt. But as the case continued on … I just thought that he orchestrated a railroad.”

A DNA BREAKTHROUGH

“In the 24 years that you’ve been in prison you’ve lost your dad, both brothers … and a sister,” Maher noted to Darryl Pinkins.

“My oldest sister, yeah,” he replied.

By 2005, Darryl Pinkins had exhausted his appeals, even though new and improved DNA tests continued to exclude him and Roosevelt Glenn from the semen stains.

The only hope left was Roosevelt Glenn’s appeal, filed in 2003 by Fran Watson, who had officially begun working as the pro bono attorney for both Pinkins and Glenn.

“Did it ever cross your mind to maybe cut a deal?” Maher asked Glenn.

“No!” he replied.

“Have you ever once given a confession?” Maher asked.

“No!” Glenn said. “I would never confess to somethin’ I didn’t do.”

Knowing that the science of DNA had worked against the men so far, Watson turned to a different science — one that actually had caught up with the case: hair analysis.

“The FBI came out in the last couple of years and said, we’re sorry, we’ve convicted people with bad hair comparison testimony,” Watson said, teaching a class. “We now know that you can’t put two hairs under a microscope and figure out if they came from the same person to a reliable degree of scientific certainty.”

But that’s not all. Remember, the hair used against Roosevelt Glenn did not have a root, and it could not be tested for DNA at the time. But by 2003, it could be tested for mitochondrial DNA —the genes you get from your mother. That test would show whether or not the hair actually came from Glenn. In a twist of fate, though when Watson got a court order to test that hair, she was given a second hair as well — and that second hair did have a root.

“They never tested that hair,” Watson said. “It had a root always. So, we test that hair.”

Professor Watson tested both hairs. It turns out neither belonged to Roosevelt Glenn, Darryl Pinkins or Bill Durden. But more importantly, says DNA expert Greg Hampikian, the hair with the root provided a new, previously unknown third DNA profile.

“We thought that was enough, because hair evidence … just like that has overturned cases all over the country,” Hampikian explained. “The FBI is … you know, apologizing for the way they’ve taught people to interpret hair. And DNA, everyone recognizes, corrects those mistakes.”

In 2008, a judge ruled that the new hair evidence was not enough to grant Roosevelt Glenn a new trial, citing the testimony of the snitch and the witness ID of Darryl Pinkins as proof of Roosevelt’s guilt. But a year-and-a-half later, after serving nearly 17 years as a model prisoner, Glenn was released from prison anyway, paroled under Indiana law for good behavior.

While in prison, Glenn wrote the book “Innocent Nightmare,” which was published after his release in 2009. Click to read an excerpt.

“They also forced you to register as a sex offender?” Maher asked Glenn.

“Right. Did you just see me flinch?” he replied. “Yeah. That’s … it hurts.”

Roosevelt Glenn with daughter Mercedes.

CBS News

It also hurt his daughters, who lost their father for nearly 17 years.

“I mean, I wish he coulda been there to help me pick out a prom dress, or say, ‘No, not –’ to that boyfriend,” said Darniese Glenn.

“Even now, you know, I struggle, you know, tryin’ to build a relationship,” Mercedes Glenn explained. “Dad’s supposed to be the one that teaches you, you know, ‘This is what you deserve. This is how you should be treated.’ And I’ve never, I haven’t had a chance to experience that.”

“My children now are 31, 30 and 25. And we don’t even know each other,” Roosevelt Glenn lamented. “And we’re very respectful and we love each other, but deep down inside, we don’t — we don’t really know each other.

“Every man needs — a father in their life,” said Dameon Pinkins. The 39-year-old is about the same age his father, Darryl was, when he was convicted nearly 25 years ago.

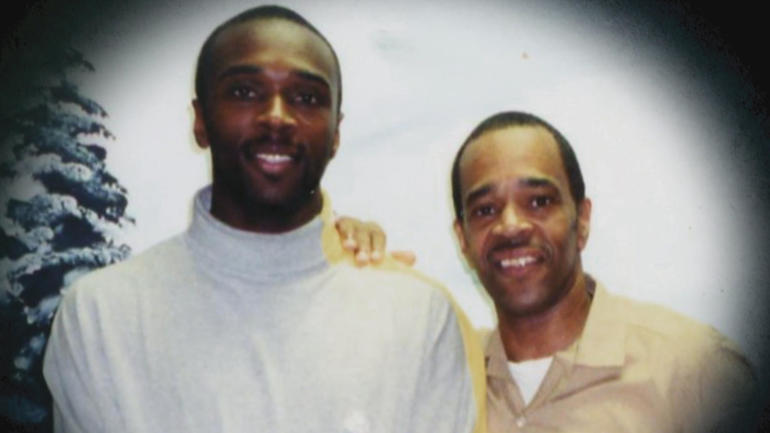

Dameon and Darryl Pinkins

“I told him he’s the strongest man that I know. … And I told him before that I needed him just as much as he needs me. Because he was actually helpin’ me,” Dameon said, overcome with emotion.

“The love I wanted to express to my children has not been able to come forth yet,” said Darryl Pinkins.

Mildred Pinkins, 84, has spent a quarter century getting desperate letters from prison. “Hey moms,” wrote Darryl, “it’s another lonely night…”

“She’d leave messages sometimes and they were haunting and would just say, ‘Just checking to see if you’re workin’ on Darryl’s case,'” Hampikian said of Mildred. “And a lotta times there was nothing I could do on Darryl’s case. But … I’d look at it and I’d think about it and I’d go to meetings and I’d asked people you know how they would approach this. And eventually that’s how we got the answer.”

It was at one of those scientific meetings where Hampikian met Dr. Mark Perlin.

Perlin had recently developed a new DNA technology he calls TrueAllele. It’s a computer program specifically designed to analyze DNA mixtures. The software allows Perlin to see profiles belonging to minor contributors to the DNA in a way that lab technicians just can’t.

“TrueAllele for example was used in 9/11 because there were so many human remains mingled,” Watson explained to a class.

“TrueAllele was being used by crime labs,” said Perlin.

“For prosecution?” Maher asked.

“Well, presumably for justice,” Perlin replied.

Perlin agreed to run the test in this case for free — a process that began back in October 2013.

“The last 25 years has been very exhausting,” said Tracey Pinkins of her brother’s case.

“But we haven’t given up hope,” said Mildred.

“We’re not — we’re not gonna give up hope,” said Tracey.

“Nope,” said Mildred.

FREE AT LAST?

In early August 2014, Fran Watson got a call from Mark Perlin. The results of the TrueAllele DNA tests were in and the news was big. Along with the original two DNA profiles, TrueAllele was able to indentify two additional DNA profiles — and neither matched Darryl Pinkins or Roosevelt Glenn.

“How confident are you that the TrueAllele test results are accurate and show that these two men, Roosevelt and Darryl were not there, they did not rape this woman?” Maher asked Perlin.

“Incredibly confident. The match statistics here were very strong and they were exclusionary,” he replied.

Remember the DNA profile from the hair with the root? It didn’t match any of the four profiles in the semen either. That meant there were now five known rapists.

“Here are five separate genotypes, five bad guys,” Watson told Maher. “None of ’em are Durden, Pinkins and Glenn.”

And TrueAllele provided even more information: three of the rapists are related.

“These three unknown profiles, who do not match any of the defendants, are brothers,” Perlin said. “There’s no brothers anywhere in the case.”

Seven months later, a hearing was set for Monday, April 25, 2016. But on the Thursday before the hearing, Professor Watson was informed there would be no hearing. After two decades of defending the convictions in this case, the prosecutor’s office conceded, and agreed to overturn Darryl Pinkins’ conviction.

The very next day, Pinkins was set to be released — an innocent man with no record.

After working on this case for three years, “48 Hours” called Pinkins’ family – and Roosevelt Glenn – with life-changing news. Their reactions captured on home video.

“Oh! Are you serious?” Tracey Pinkins exclaimed over the phone. “Oh, Darryl’s getting’ out tomorrow!” she told her mother.

“Are you serious?” Glenn replied, wiping away tears.

“48 Hours” was there the next day, when Pinkins —his hands still cuffed—finally heard the news he’s been waiting for, for nearly 25 years.

Professor Watson and Darryl Pinkins hold hands as he learns he will be released from prison

CBS News

“Fifty feet across from this building is your mom, some of your kids, sisters, nephews, and they are so anxious to see you,” Maher told Pinkins.

“I feel like I’m about to explode. But I’m so thankful,” he said smiling.

We all waited that entire day for Pinkins to be released, all on the edge, but it never happened.

Apparently the paperwork hadn’t been signed in time, so a man, now innocent in the eyes of the law, would remain locked up for the weekend.

“This is not what you do to people who have put up with 25 years of absolute injustice and they have a court order in their hands to say, ‘Free this man,'” said Hampikian.

That Monday, there were even more people there to see Darryl Pinkins released. And thanks to jail administrator Mark Purevich, “48 Hours” got an extraordinary look at Pinkins’ reentry into his world.

“Had you seen him dressed in civilian clothes before?” Maher asked Watson.

“No, never,” she replied.

“He had a different stance?”

“Yeah …you already saw the different person,” Watson told Maher. “You got to see Darryl be a man again — you know, be a proud man — and leave– feelin’ exonerated, knowing that the world would know he didn’t do it.”

“Here we go,” Maher told Pinkins. “This is your moment Darryl…”

For the first time in more than two decades, Darryl Pinkins – now 64 years old – was actually able to hold his mother and his children.

But Pinkins wasn’t alone. For him it was also about his partner in innocence – Roosevelt Glenn.

“Is this the first wrongfully convicted case that TrueAllele has been responsible for overturning the conviction?” Maher asked Watson.

“Yes,” she replied.

“Precedent setting?” Maher asked.

“Clearly,” Watson affirmed. “…and hopefully open up the eyes of other lawyers that in these mixture cases it’s now time to go back and try again.”

“Feels like this day, it was meant to be,” Pinkins addressed a waiting crowd after his release. “I feel like this is a new beginning.”

Shortly after these men were convicted, Lake County Prosecutor Bernard Carter took office, and has vehemently fought every appeal in this case. One month after Pinkins’ release, Carter finally agreed to an interview.

“Has this office, have you gone back and looked at the case all the way through to say, ‘Did we miss something here?'” Maher asked the district attorney.

“Yeah — we have done that. And — not really. Only thing … we feel that we got … conclusive evidence once that last DNA profile was, we felt absolutely that something has to done,” Carter replied.

“But all the way up until then—” said Maher.

“But all the way up until today, it was an arguable … case, yes it was,” said Carter.

With one pretty significant exception.

“Well, when you look at that identification, that … identification was, in my opinion, very flawed,” said Carter.

After personally taking the time to review the entire case file, Carter — who shook Pinkins’ hand the day he was released — says he is very bothered by the victim identification which kept Pinkins behind bars for nearly a quarter century.

“If that hadn’t happened, that ID, would Darryl Pinkins have spent 24-and-a-half years in prison –” Maher asked Carter.

“I don’t think he would have, I don’t think he would have,” he replied. “Absolutely not, no.”

“And if Darryl Pinkins, who was tried before Glenn had not been convicted, would Roosevelt Glenn had gone?” Maher pressed.

“No, it’d failed, too, probably,” said Carter.

Detective Mike Solan strongly disagrees and remains convinced that Darryl Pinkins is guilty.

“The prosecutor said the words, ‘He didn’t do it,'” Maher told Solan.

“Yeah,” he replied.

“Right. He didn’t do it,” Maher remarked.

“Does that make him right?” Solan asked.

“Does it make you right? To say that he did?” Maher asked.

“No, but we got people on the other side say he’s wrong,” Solan replied.

Not the mayor of Gary, Indiana. Karen Freeman-Wilson gave Roosevelt Glenn a job when he was paroled.

“Is it a fair question to ask you if you think race played a role in this case?” asked Mayor Freeman-Wilson.

“I certainly think it did in the investigation and the way that — Detective Solan viewed these men, the fact that there were black men charged with raping a white woman,” she replied.

“Ask them to produce any evidence to show that I was racist on this. I talked to them, I gave them the Miranda warnings, I never threatened any of ’em. I followed the evidence,” Solan told Maher. “I never used the word nigger to them. I never insulted ’em using that word. …Have I ever used it in my life? Earlier in life I have. I haven’t used that word in 20 years.”

“Thank God for Fran,” Glenn said of Watson. “She’s an angel sent from above.”

“Fran is a lifesaver. To me she’s a lifesaver,” Pinkins said. “She is.”

“This case overall… coulda been prevented … from day one. And it’s sad to say that those that are in charge, in power … need to get back to ethics, good ethics,” said Glenn.

EPILOGUE

In early 2017, Roosevelt Glenn’s conviction was finally overturned.

“…and now I can shout, I can scream, I can dance if I want to, and I want to thank all of you,” he said aloud in church.

Glenn’s name has now been expunged from the federal sex offender’s registry.

On April 25, 2017, exactly one year after being freed from prison, “48 Hours” checked in on Pinkins, who is living on his own and still trying to adjust to life in the 21st Century.

“It’s been an eye-opening. It’s like I’m into a new realm, a new world really from cell phone technology to dealing with new people,” he said.

After months of hunting for a job, it was Mayor Karen-Freeman Wilson who, once again, came to the rescue — hiring Pinkins as a maintenance worker for the City of Gary.

“It makes me feel like a man. You know it’s nice to take somebody out to dinner and you pay, not her. I’m old-school,” said Pinkins.

Ironically, Roosevelt Glenn and Darryl Pinkins now work together again.

On July 28, 2017, six months after finally seeing her son Roosevelt exonerated, Sally Glenn passed away, just shy of her 90th birthday.

Pinkins and Glenn will be filing a civil rights lawsuit that will include the state crime lab and Detective Solan.