“Look at that plane!” said Lonnie G. Bunch III, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, of Charles Lindbergh’s “Spirit of St. Louis.” “Look how little it is. It is a tiny plane!”

Bunch is enamored of American history, and he’d like us to join him in learning from the past, for better and for worse.

“It’s my job to tell the unvarnished truth, to illuminate all the dark corners of the American past,” he said. “In a museum that’s gonna talk about difficult issues, you try to find the right tension between those stories that are gonna make you cry – ’cause you better cry – but there are also the stories that give you that resiliency, that make you smile.”

Smiles, resilience and tears are at the core of the story of Lonnie Bunch. In June he was named Secretary, in charge of 19 museums, 21 libraries, the National Zoo, 7,000 employees, and a budget of $1.5 billion – and a mission that he believes is nothing short of monumental.

“What’s clear to me is that the Smithsonian is part of the glue that holds the country together,” he told CBS News national correspondent Chip Reid. “Culture is so important. Culture is something that sometimes is seen as dividing people, but in my mind, culture holds us together – the common cultures we have, the opportunity to find common ground.”

There are an estimated 155 million objects in the Smithsonian’s collections. We asked Bunch to choose four that have special meaning for him.

Some have intensely personal connections, including the “Spirit of St. Louis” (now on display the National Air & Space Museum), which inspired him as a child.

“My father was a scientist. And as a kid, we would come down to the Smithsonian because it was a kind of safe place that African-Americans could go. And he’d take me into the Arts and Industries Building and he’d talk about Lindbergh.”

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh made the first solo, non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean. He was just 25 years old.

“What’s so amazing about it is what it took for him to not panic, to keep himself under control as he flew for those 33-and-a-half hours,” said Bunch. “And then the wonder of it, actually making it.”

Can the plane still fly?

“It doesn’t fly, but it looks like it could,” Bunch said.

Lonnie Bunch grew up in Belleville, New Jersey, where his family was the only African-American one in their neighborhood. He loved baseball, but after one game in a neighboring town, he said, the white kids suddenly attacked him, and chased him with baseball bats.

“I remember that I was exhausted and that I just couldn’t run anymore, and basically just collapsed in front of this house,” he said. “And then a little girl comes out and she basically said, ‘Get off my land.’ And I thought she was talking to me. Instead, she stood between me and the mob, and basically protected me.”

The girl who came to his rescue was white. “And it taught me so much. Because it made me realize: never generalize, never assume, based on the color of one’s skin.”

Personal experience helped Bunch develop a passion for history, which he calls his “teacher and protector.” “For me, history was both a way to understand the American past, but also a way to help me understand why some people treated me wonderfully and some people did not,” he said.

Bunch is the first African-American leader of the Smithsonian in its 173-year history. “I’m not unaware of the symbolic power of this for many people,” he said.

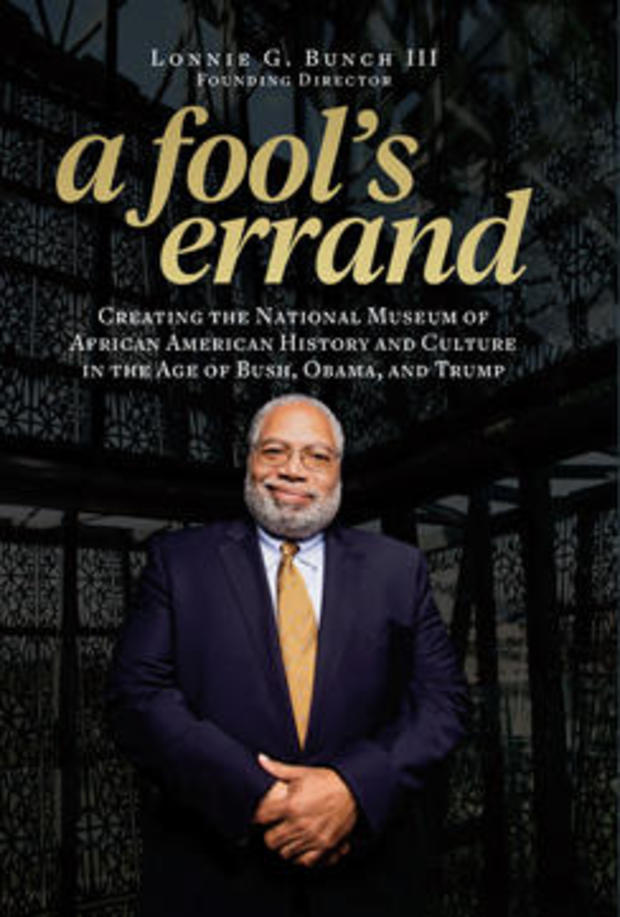

Over the years Bunch returned again and again to work at the Smithsonian: Air & Space in the late 1970s; American History in the late ’80s; and recently he spent 14 years overseeing the creation of the new National Museum of African-American History and Culture, which opened three years ago, and is the subject of his new book, “A Fool’s Errand.”

Reid said, “You essentially started with nothing?”

“We started with a staff of two,” said Bunch. “We had no idea where the museum would be. We had no collections. We had no money. This museum collected 40,000 artifacts, of which 70 percent came out of basements, trunks, and attics of people’s homes.”

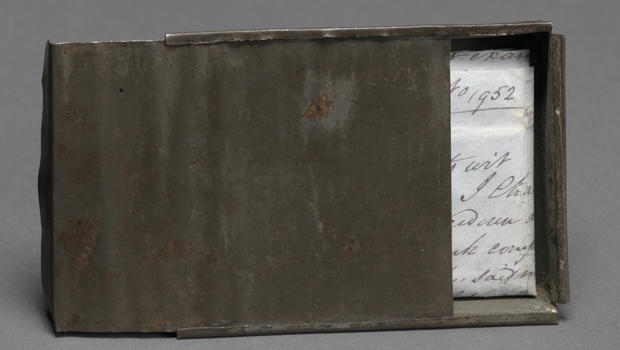

One of his most-treasured objects? A tin box, which he calls a “tin wallet.” It was hand-made by a freed slave, Joseph Trammell. In the wallet, Trammell carried papers, proof of his freedom. “Without that paper, you can be enslaved again,” said Bunch. “So, the key is to protect it and to keep it.”

Reid asked, “In putting this museum together, did you get some pushback from some people who said, ‘Let’s not emphasize slavery. Let’s emphasize the positive things and the heights that we’ve reached’?”

“Oh, there was an amazing amount of, oh, let’s just say ‘guidance’ that people wanted to give me,” he replied. “When we did surveys, the #1 question people wanted to understand was slavery. And the #1 question they didn’t want to know about was slavery. So, I knew that slavery and freedom had to be at the heart of this museum, because it’s at the heart of what America was and what America still is.”

One of the four objects Bunch selected took Reid by surprise: a statue at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which he’s visited for decades. “When I was an undergraduate at Howard, this was my escape. I’d wander through this museum, this very museum, and be made better,” he said.

Historian and philosopher Henry Adams commissioned the great sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to create a memorial to his wife, Marian “Clover” Adams, a photographer who took her own life at the age of 42.

“There was something so powerful about it, and poignant,” Bunch said of the statue (a bronze replica of which is at the museum). “You can look at that face, and you could feel his pain.”

The fourth item Bunch selected for us is the lunch counter from a Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina, which he helped bring here. “It is the lunch counter that really sparked a revolution,” he explained.

On February 1, 1960, four African-American students sat at the whites-only counter and asked to be served. They weren’t. “And that excited people around the country to say: This is wrong. How could it be fair that somebody could not simply sit at a lunch counter and eat?” Bunch said.

Across the country, more than 3,000 people were arrested, until the lunch counters were finally desegregated six months later. Again, there’s a personal connection for Bunch: “So, it’s gotta be 1957, 1958, I’m taken to North Carolina to visit relatives. Now, not Greensboro, but Raleigh.”

He was allowed to sit at the Woolworth’s counter in New Jersey, so why not in Raleigh? “I’m sitting at this lunch counter and suddenly these white hands pick me up and take me over to the standing part where only colored people could stand. And I remember being dumfounded. And they served me a hamburger. And the taste was never the same. I never went back to Woolworth’s after that.”

Lonnie Bunch thanks his parents and his grandparents, for preparing him to face the world, and, ultimately, the job he has just begun. One thing they told him was that African-Americans had to be twice as good to get half as far.

Reid asked, “Do you feel that you have to be twice as good?”

“I feel that the burden of race, the burden of expectation is often heavier on African-Americans,” he said. “I didn’t have the luxury to screw up.

In my office there’s a picture of an enslaved woman carrying a big hoe and a basket, and her knuckles are swollen, her dress is tattered, and yet she’s looking up and moving forward. To me, being African-American means you look up, you move forward, no matter how heavy the burden.”

Click here for in-depth commentary and video of Lonnie Bunch on objects from the Smithsonian collections.

BOOK EXCERPT: “A Fool’s Errand” by Lonnie G. Bunch III

For more info:

Story produced by Jay Kernis.