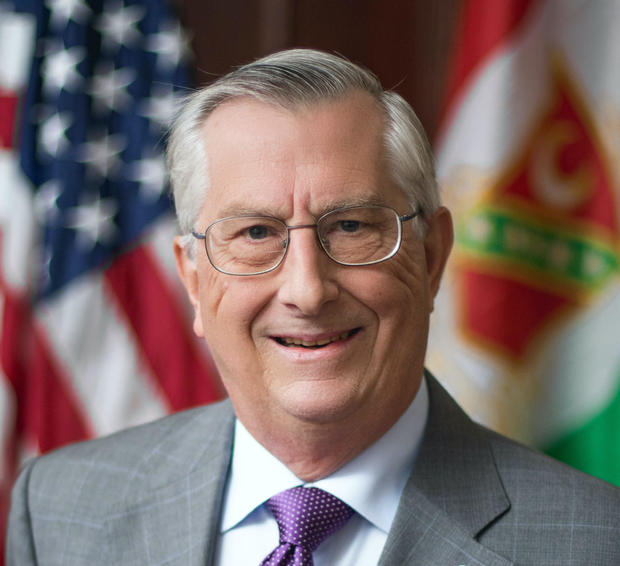

In this episode of “Intelligence Matters DECLASSIFIED: Spy Stories from the Officers Who Were There,” host Michael Morell interviews Martin Petersen, former senior CIA intelligence officer and Asia expert who spent over three decades at the agency. Petersen recounts the agency’s early assessments of unrest that led to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in China. Morell and Petersen discuss the training CIA analysts receive and Petersen shares the remarks he would make to all entering analyst classes. “Intelligence Matters DECLASSIFIED” is new series dedicated to featuring first-hand accounts from former intelligence officers.

Highlights:

On China’s political dynamics during Tiananmen vs today: “I think the challenges that we identified in those papers, what, 40 years ago, actually are still valid today. The Party’s dilemma is this: ‘We have a monopoly on power. How do we hold off pressures for political reform, such as we’re seeing out of Hong Kong? Marxist Leninist ideology doesn’t cut it anymore. So our legitimacy, our monopoly comes down to two things: Building the economy, economic prosperity, and protecting China’s global interests.’ And I think the aggressiveness you see in Beijing are both economic issues and its role internationally, economically. And what it’s doing militarily in foreign policy are both a reflection that that’s what their power rests on.

Excerpts from remarks to entering CIA analyst classes:

“The demands on us are great. Hours can be long. Flexibility is essential to success here. And there’s a sense of service and sacrifice and patriotism – although it’s not talked about much.

There will be late dinners and missed events in the course of your career. There will be times when it could be hard to read a newspaper or watch the news, perhaps because what they have to say is incorrect; sometimes because what they have to say is too true. These things will take a toll on you, and on your family.

But there are rewards, too. And none greater than the knowledge that what you do matters. The work is important. You will make a difference. I’ve seen it time and time again over the course of my career. Time and time again, the men and women this building have pointed the way. And in so doing, made the world a little better, a little safer.”

Download, rate and subscribe here: iTunes, Spotify and Stitcher.

Intelligence Matters DECLASSIFIED: Martin Petersen – Transcript

Producer: Olivia Gazis

MICHAEL MORELL: Marty, welcome to Intelligence Matters, I can’t overstate how nice it is to have you on the show.

MARTIN PETERSEN: Michael, thank you very, very much for inviting me. I’m honored, truly.

MICHAEL MORELL: So, Marty, as you know, we’re going to talk about how CIA analysts approached the Tiananmen crisis in China in 1989. But before we do that, I’d like to ask you a little bit about your career. So I’d love for you to share with our listeners how you ended up at CIA, how you ended up as an analyst, and how you ended up spending a chunk of your time working on East Asia and China.

MARTIN PETERSEN: Well, ‘There is a story,’ he said, but with a point actually, too, Michael, it really starts with a couple of happy accidents.

I was in college junior year working my way through school. I needed an upper division political science course that started 7:30 in the morning so I could make my job by noon, OK? And the only course they were offering was something called ‘Governments of Communist Asia.’ So I took it and I loved the course. I loved the professor who became a mentor of mine. And I proceeded to take all the other Asian courses I could get – history, art and that sort of thing.

So by the time I was graduating, I decided I wasn’t going to go to law school. I was going to become an Asia expert. I got a grant to go to the East-West Center in Honolulu. This is in 1968. And about a year later, 1969, I was drafted and I did two years in the Army, a year in Vietnam as a NCO in the infantry. And when I got back on campus in 1971, well, it was ‘Hate the War, Hate the Soldier.’ And I really couldn’t stand being there, knew I couldn’t be a college professor. So I went around looking for another job. Took the State Department exam, passed that.

And a friend of mine who had been in Air Force intelligence in Thailand came up, said, ‘Hey, Marty, there’s these other guys you need to talk to.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’

‘Well, it’s the CIA. They’ve got this one page little form. You mail it in and if they like what they see, they’ll give you a call and talk to you.’

I said, ‘OK, great.’ So I mailed it in.

And sure enough, about three weeks later, I get a phone call, Michael, and the phone call goes exactly like this:

“Hi. I’m Ed. Got your form. Like to talk to you. You want to talk to me, you’ll be at this place, on this day, at this time. Got it?’

‘Got it.’

Click.

OK. So I show up at the appointed time and place. It turns out to be a rickety old building down in the Honolulu Harbor area. I go up to the room and I knock on the door and I hear this voice saying, ‘Come in.’

And I open the door, and Michael, there’s nothing in the room. There’s nothing in the room but a card table, two folding chairs and a guy I presume to be Ed. Okay, so. So I sit down and we start chatting. I keep waiting for him to tell me about the job. And after about a half hour, he’s basically talking about my experiences in Vietnam, grad work and says, ‘Well, I’ve heard enough.’

And he reaches into his his briefcase and pulls out the old paper application. I don’t know, maybe you saw it, took like thirty-three pages, thumps it on the table and says, ‘Fill it out if you’ve got the guts and mail it. And by the way, don’t call us. We’ll call you.’

And I kind of stumble out of the room going, ‘I don’t know how to call you!’

So I graduate. I go back to Phoenix, Arizona, and in March I get this phone call and this phone call goes like this:

‘Hello. This is the Department of the Army. Do you know who this is?’

I’m going, ‘Yeah, I think so. I didn’t apply to the Army.’

And they said, ‘Well, look, we’d like you to come to Washington for a week of interviews. And I said, ‘Great.’

‘We’ll set it up.’

Now, you know, I’m working a minimum wage job. I’m married to Irene. I’ve got no money and I know I need a suit. So I’m going to tell you something now and I want you to be very, very kind to me when you picture this, Michael, OK? Because it’s 1972 if you’ve seen the TV shows. I go out and buy an electric blue suit with bell bottom pants, a paisley shirt and a purple tie.

I fly in to D.C. with 20 bucks and a MasterCard to last a week. I go to the motel where they told us to stay, show up for the first deployment the next day, go to the receptionist and she looks me up and down with the gimlet eye and she says, ‘Young man, exactly how much money do you have in your pocket?’

I got a ten dollar bill and a MasterCard to last a week.

She’s saying, ‘OK. Before you leave today you come back here and you see me. You don’t go anywhere. You see me. OK?’

I’m thinking, ‘Oh, yeah, I’ve been here five minutes. I’ve failed the means test.’

OK, so I come back at the end of the day and she holds up this blue ticket and she says, ‘You see this blue ticket?’

I said yes.

She says, ‘I want you to go down and stand on the street corner and I want you to get on a blue bus. The blue bus will say, ‘Blue Bird.’ You are to get no other bus. And you do what the driver tells you.’

I said, ‘OK.’

So I’m down there, there’s a half a dozen people. They all get on the bus, seem to have chains and badges. I hold up the blue ticket. The driver says, ‘Get on the bus behind me.’ And we take off. And you know where we go? We go to CIA headquarters. Wow.

OK so everybody gets off the bus. I look at the driver, say, ‘What I do?’

‘Go right in and the guard will stop you to tell you what to do.’

So I go and the guard tells me sit down. About five minutes later a lady comes around the corner. She takes me to her office. She says, ‘Do you have your plane ticket.’ I give her a plane ticket. She opens a cash drawer, Michael.

And she pays me for the plane ticket. And she pays me six days per diem.

Now, when I flew in, they told me that they would pay for it, but it’d take a couple of months. And I left there thinking, ‘They don’t even know they’re going to hire me. But they’re making sure that I’ve got enough money to get through the week. This is the kind of place I want to work.’

Point one: The image in fiction and movies is that it’s a pretty cynical, hard, uncaring place. And you know and I know that that’s simply not the truth. They look after their people. They were looking after me before they even hired me. And we look after the people who work for us in the field.

The second point out of this story is the hiring process has changed a lot. And for the better; it’s much more open now. But I think most critically, at least from where I stand, it’s more diverse. It’s more inclusive. And I think if you’re going to have a secret intelligence organization it’s got to look like America and it’s got to reflect the values of the country.

And so that’s how I ended up there. I worked in Asia for 20 some years before I ended up as ADDI, Associate Deputy Director for Intelligence and then the first Human Resources officer and then Deputy Executive Director and Executive Director.

MICHAEL MORELL: I think, Marty, that that is the best answer to the question, ‘How did you end up at CIA?’ that we have ever heard here on Intelligence Matters.

So we’re going to get to Tiananmen. But I do want to embarrass you for just one second. I do want to tell my listeners that I was extraordinarily lucky that your career went the way it did because you were the most important mentor that I ever had. Or the second most important mentor if Tom Elmore is listening. And for my listeners, that’s an inside joke. But seriously, Marty, I learned as much from you about analysis and about management and leadership as I did from anybody else. I just want everybody to know that.

OK. So let’s chat about Tiananmen. Where were you on the 15th of April, 1989, when the crisis began?

MARTIN PETERSEN: It was actually my first day on the job as Deputy Director of the Office of East Asian Analysis.

I had spent four years previous as Chief of the China division, and a year before Tiananmen the Deputy Director for Intelligence asked me to spend a year at the Office of Training and Education, looking at analytic training programs and seeing if I could come up with some ways to make that training more effective. So I had just completed that assignment. I showed up on the 15th. And it all started.

MICHAEL MORELL: So before we get into to what the agency actually did, what the work of the analysts was. I’d love to have you kind of summarize what happened in China between the 15th of April and June 1989.

MARTIN PETERSEN: OK. A couple of points of context, just to kind of kick this off, because they’re important. The first is that Deng Xiaoping kicked off his reform program in December 1978. Actually, 10 years before this. And two of his key allies were Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang. There was a lot of opposition to Deng, but Deng prevailed, and his reforms were basically focusing on opening up the economic system. But there was a lot of pressure as well to relax political controls. And Hu Yaobang is pretty sympathetic to that. But Deng isn’t. And certainly the Party elders aren’t. And eventually there’s a falling out between Deng and Hu and Hu is ousted from power in January 1978.

OK, fast forward: Spring, 1989. Deng’s reforms are paying off, but there are very clear winners and losers. There’s also a lot of corruption, inflation, nepotism and a lot of resentment.

At the same time, it’s important to remember that communism is collapsing in Eastern Europe and the Russians are in retreat. So for the PRC leadership, this is a pretty frightening time. Their world is kind of shaking. So Hu dies on the 15th, and there’s a spontaneous outpouring of sympathy, particularly from students, and they begin to gather not only in Beijing, but in other cities all across China.

And it’s important to remember that these children are the children of the elite. They’re the sons and daughters of Party officials, government officials, military officials who just didn’t get into those universities unless you had those kinds of connections. And students being students, after a couple of days, they begin to draw up a list of demands. And among the demands are more freedom of the press and investigation of corruption — which is basically an investigation into the families of senior leaders — higher pay for intellectuals. And they also demand to see the premier Li Peng, who is an elder and a hardliner. Now the Party is getting pretty concerned.

Students are refusing to leave the square. They’re starting to organize, and the leadership is divided. Zhao wants to push a softer line. Li Peng, a hard one.

MICHAEL MORELL: And Zhao at this point is in what position?

MARTIN PETERSEN: He is Secretary General of the Party. And in the back of everybody’s mind, Michael, is memories of the Red Guards rampaging during the Cultural Revolution, students being very frightening.

OK, so the hardliners prevail. And on April 26, they put an editorial in People’s Daily that says that the students in the square are basically engaging in anti-Party activities, which, of course, only fires up the students. And the day after, on the 27th, something like 50,000 to 100,000 people marched through the square in support of the students. Party’s frightened; backs off, tones down the rhetoric, even admits some of the gripes from the students are legit, and things de-escalate a bit.

Some of the students actually leave the square, but there’s kind of a hard core of student leaders who press for more confrontational tactics. And on May 13th, they start a hunger strike. And that really galvanizes popular support for the students. In fact, four days later, about a million people from all walks of life in Beijing start to parade and demonstrate peacefully in Beijing.

This seems to have been the final straw for Deng. Zhao is criticized at a series of meetings. And on 17 May, Deng makes the case to impose martial law. Zhao goes into the square on the 19th, pleads with the students to end the hunger strike and leave. He has absolutely no impact other than to further anger Deng. Martial law is declared on the 20th. Some troops actually start to move into the city.

But this is where you get the protesters pushing back and you get that great photograph of that young man standing in front of the tank and moving. The Tank Man. So the troops go back to the barracks, and the leadership drops out of sight.

And there’s a series of very tense meetings in late May and early June. Zhao and the moderates are ultimately removed from office; Deng and the elders in the military make the decision to use force. They give the order on the 3rd of June. Troops move in about 10 o’clock and the killing starts.

And even to this day, there’s no accurate figure for the casualties. They range from a few hundred, which was the regime’s official position, to several thousand. But we just don’t know.

MICHAEL MORELL: Well, that’s quite a story, Marty. That sets up perfectly how the agency saw all of this at the time. So first question, how did we assess Chinese politics and Chinese stability in the run up to Hu’s death?

MARTIN PETERSEN: I think we had a pretty good understanding of the dynamics. Deng was clearly the key decision maker, but there were other power centers — Party elders. In fact, the military was not entirely on board with all of Deng’s programs. And again, this was a frightening time. Eastern Europe was coming apart. Deng was changing a system that most Party and government guys were not only comfortable with, but actually been giving their lives to. They were revolutionaries. And they were creating winners and new losers. And there were just a lot of people that didn’t understand what was going on, and were lost.

I was part of this delegation that met with a Party committee at one of the large iron and steel factories in China. And we we’re talking about Deng’s program and how they were implementing and so on and at the end of it, the head of our delegation turned to the Party committee and said, ‘Well, you know, we’ve got these experts from Washington. They’ve been asking you questions. Would you like to ask them anything?’

And they all huddled for a moment. And then they came back and said, ‘Yeah. How do you make a profit?’

And I’m going, ‘Oh, boy, has Deng got his hands full here.’

MICHAEL MORELL: Yeah. So what was our early assessment of the protests? How did we see them? Did we correctly identify that they could get out of hand?

MARTIN PETERSEN: Yes. Yes, we did. And one of the things that I think we knew from the beginning was that if this thing persists, it’s going to end badly. I think there was a chance maybe to defuse things a little bit on April 26th. But that People’s Daily editorial, the fact that Zhao and his reformer allies were on the defensive and that hunger strike, I think pretty much destroyed any chance of a peaceful ending.

At a minimum, we thought there would be mass arrests and that the leadership would use force if pushed. And there was a lot of press in China at this time, too, Michael. And the other thing that was going on is that Gorbachev was about to visit. This is a first Sino-Soviet summit since late ’50s, early ’60s. And the press were all over the square. They were talking to students. They were impressed by the students and they had this Eastern European frame of mind or frame of reference that maybe China was going to go down as well. And they were a lot more upbeat about a possible happy ending than than we ever were.

MICHAEL MORELL: So Marty, you talked about how this was this was not only the Party against the protesters, but it was also different factions in the Party against each other. You mentioned that a couple of times. And I’m wondering if we saw those rifts inside the Party in real time or whether it it took some time for us to see them.

MARTIN PETERSEN: No, I think we saw them actually very early on, Michael. And I go back all the way to a paper that we did in 1978 when Deng’s reforms were first starting.

And we look at the program that he was proposing, and we looked at the challenges it faced, but also the likely impact on the system. And I remember writing a brief introduction to the paper saying that basically if Deng’s reforms take hold — and it was a big, big if because we weren’t sure — this was going to be the most significant change in China since the fall of the Qing dynasty.

‘Oh, how can you say that? There was a 1911 revolution and there’s a ’49 revolution…’ I said, ‘Look, you’re going to get new winners, new losers, new voices, new stakeholders. And the Party is really going to have a hard time maintaining control of this reform process. Particularly there’s going to be demands for political change as well as economic change.’

And in ’83 we did this paper on Hu Yaobang, looking at his style and his politics and his strengths and weaknesses. And one of the things that we said in that is that his chances of succeeding Deng really hinge on two things: One, staying on the good side of Deng and outliving the elders. And neither of those happened.

And then when Hu fell in ’87, we did another paper that looked at the leadership dynamic. And I think the challenges that we identified in those papers, what, 40 years ago actually are still valid today. The Party’s dilemma is this: ‘We have a monopoly on power. How do we hold off pressures for political reform, such as we’re seeing out of Hong Kong?’

‘Marxist Leninist ideology doesn’t cut it anymore. So our legitimacy, our monopoly comes down to two things: Building the economy, economic prosperity, and protecting China’s global interests.’

And I think the aggressiveness you see in Beijing are both economic issues and its role internationally, economically. And what it’s doing militarily in foreign policy are both a reflection that that’s what their power rests on.

MICHAEL MORELL: So, Marty, when the lines were drawn inside the Party, was there any doubt about who would end up on top?

MARTIN PETERSEN: No, I don’t think so. We felt that the key was Deng’s ability to make sure that the military was on board. And there were a lot of people in the {arty, the elders and particularly, that were, like I say, unhappy with where Deng wanted to go. The military, too, because Deng told the military early on, ‘You’re not going to benefit from these economic reforms for the first 10 years. We’re going to build the economy and then we’re going to build the military after that.’

And plus, you had all the officials who still had ties to the Gang of Four and the leftists and all those Red Guards in the countryside that weren’t coming back. Plus there were a lot of people that wanted to go back to the 1950s. A lot of people that didn’t want to go into the 1980s and 1990s.

MICHAEL MORELL: So, Marty, it’s great to kind of walk through how we saw this, and I think it gives our listeners a sense of what analysts at CIA actually do. This might be kind of a hard question, but do you think there’s any lessons from how the agency looked at China in the years leading up to Tiananmen and then how you handled the Tiananmen crisis for analysts today?

MARTIN PETERSEN: I think there is, Michael. You know, we deal with these kinds of events as analysts all the time. It’s unclear where we’re going in many of these instances because the information is contradictory or it’s wrong or it’s incomplete. And I think when we look at where analysis goes wrong, I think it’s it’s generally because one of three things happen. And they are lessons for today.

One is that we don’t have a very good understanding of the organization that we’re trying to analyze. Or two, we don’t understand the individuals in that organization who are making the decisions. Or three, we don’t understand our own analysis. I think there are some very simple questions — I’ve got to kind of walk up to it. OK.

There’s a real simple set of questions that I think intelligence officers do in collection and policymakers need to mole continuously or they’re going to miss something significant with the organizations.

The three questions are pretty simple. How do you get to the top? What’s the preferred method of exercising power and making decisions? And what are the acceptable and unacceptable uses of power? If you don’t have a feel for how the system works and what the answers are to those questions, then you have no idea how the game is played.

With individuals, I think it’s important that you understand how they assess the situation, how they see their options, what their tolerance for risk is, and what they believe about U.S. intentions, capabilities and will. And in particular, what’s their definition of an acceptable outcome. Unless you understand those ideas or understand how they see those things, then you have no idea how your policy initiatives are going to have an impact on them.

Now, to get to your question, ‘We don’t understand our own analysis?’ I believe strongly that one of the worst questions you can ask an analyst is, ‘How confident are you?’ Because they’re good analysts. They look at the information, they weigh the data. They say, ‘I’ve caveated things. I’m pretty confident.’

I think the question we ought to be asking ourselves is, ‘Where am I most vulnerable to error? Might not be wrong, but where am I on the weakest ground?’ If you’re asking that you come out in a very different place than when you ask if I’m confident.

The other thing that you need to ask yourself periodically is, ‘What am I not seeing that I should be seeing if my line of analysis is correct?’

And lastly, Michael, this is the big one. I think this is at the root of more intelligence failures than anything else. If you ever find yourself thinking or saying out loud the following, the hair needs to stand up on the back of your neck: ‘It makes no sense for them to do that.’ …Which is a pretty good indication that you don’t understand the organization you’re trying to analyze or the people that are running it. And I think those are the lessons that I would take away from looking at a Tiananmen, Iraq WMD or any a number of these other instances that we’ve had to deal with.

MICHAEL MORELL: Great. Marty, I think everybody now sees why you were my mentor. So just a couple more questions about Tiananmen.

The first is, I think it was 12 years after Tiananmen in 2001, that secret Party documents about the crisis were smuggled out of China and published. And I was wondering — I’m sure you read those. Were those consistent with our analysis or did they change the way that we looked back on it, do you think?

MARTIN PETERSEN: I think they were pretty consistent, Michael. I have to tell you, at that point, by 2001, I was, I think, Chief Human Resources officer. So I was out of the analysis business and out of the China business specifically. But I don’t think there was anything that came out in those documents that really surprised us. I think we had a pretty good grip on it.

MICHAEL MORELL: OK. And then George H.W. Bush was the president at the time. And he was a great consumer of intelligence. He actually got his PDB every day, he read it. He saw a briefer. He asked a lot of questions. Right. So what was he looking for, do you think, from our analysis?

MARTIN PETERSEN: Well, he was a pretty, as you said, a very, very sophisticated consumer of intelligence, especially on China. Remember, he had been ambassador to China. Ambassador to the U.N. He’d been Director of Central Intelligence.

And I think, as events began to unfold, the initial focus of the administration was a lot like the press at that point. Were we seeing it in Tiananmen a reflection of what we were seeing in Eastern Europe? Was this going to lead to collapse somehow? And I think we quickly convinced the administration that that was unlikely. And we raised early on that there was a prospect that if this did not end quickly, this is a regime that was prepared to use force.

And President Bush in particular, and the people around him listened, were convinced. And then their focus changed really to the safety of Americans in China and particularly the safety of Americans in Beijing.

I remember at some point in the crisis, probably late May, maybe after the leadership kind of dropped out of sight with those meetings around the 20th of May, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence asked for a briefing. And so I went down to do it, along with the head of our China unit and a State Department officer from the China Desk. And when we got down there we found out that the SSCI had invited any senator that wanted to sit in on the briefing. And so we had literally two-thirds of the Senate there. And I laid out our take on the situation, including the possibility it could end badly with the use of force. Senators asked us a few questions and they turned to this poor State officer and they wondered what State Department was doing to prevent the Chinese from using force. Where were all the Americans in China? How many were in the square? I mean, they just shredded this poor fellow.

And it drove home to me something that our mentor Tom once told me, Michael. And he said, ‘Marty, you know what the difference is between CIA and everyone else?’

I said, ‘No, Tom, what’s the difference between us and them?’

And he says, ‘Well, we deal with the world as it is and everyone else in Washington is trying to change that world.’

And I think this in no small measure accounts for the occasional disconnect that we see between the intelligence community and the policy agencies, including the White House. And that’s every White House. Sooner or later, someone says, ‘You’re not really helping us. You really need to get on the team,’ or whatever.

And I do think a major part of being an intelligence analyst is helping these policy communities understand how they can steer events. I don’t think it’s enough to tell them what’s going on or why or even what it means, although that’s important. Where they really need help is telling them what factors are the most important and whether there are any levers out there that they could pull or push to kind of guide events in a direction favorable to U.S. policy without being policy prescriptive. I think we do a very good job of what’s going on and why is going on or what it means. But we don’t do a very good job of helping them think through what options they may have.

MICHAEL MORELL: OK, last question, Marty, on Tiananman, from a sort of big picture perspective. How did the crisis change China? What was the long term impact of what happened?

MARTIN PETERSEN: Well, personally, I doubt there was ever a Prague Spring in China’s future, but I think Tiananmen put a finish to any significant loosening of that political system, especially as it related to the Party’s monopoly on power and its control over messaging. Certainly the current leadership is not inclined to move in that direction. It’s a leadership of arrogance and hubris and insecurity. I think the response to the demonstrations in Hong Kong is the latest indication that they’re not going to tolerate any challenge, whatever its form, or entertain any real loosening of control. So maybe there’ll be a loosening some point down the way, but I think Tiananmen froze political change at least until today.

MICHAEL MORELL: Okay, Marty, that was fantastic on Tiananman. I want to ask you just one more thing. And I want people to know that you were the father of the way we train analysts at CIA.

Something called the Sherman Kent School, which is the agency school for training analysts, and something called the Career Analysts Program, which is the initial training that all analysts go through, would not exist today if it wasn’t for you.

And I know that during your time at the agency that you would meet on the very first day with every new career analyst program class, and that you would share with them what you thought the most important things that they needed to know at that moment of their career. And I would love if you could share with us what you told them.

MARTIN PETERSEN: OK, Michael, I have given that short speech, I think, over 100 times. The first time, actually, in May of 2000. And you’re right, I do believe that it captures what I believe about the agency and the Director of Intelligence, what we ought to be all about.

So imagine both you, Michael, and our listeners, that you’ve entered on duty at CIA.

You’ve been through all the first weeks of orientation and whatnot. And now you’re going to begin your your training as as analysts. And it’s Day One, Hour One. And I meet you I meet you in the lobby of the CIA. You’ve seen in a million movies. There’s about 25 or 30 of you.

You’re standing on the seal with your back to the doors and you’re facing the atrium. I walk in, I introduce myself and I say, ‘Welcome.’

‘I want to take a few minutes to tell you why you’re standing where you are, and why your education in intelligence starts here. Look to your left. That’s a statue of General Donovan to whom we trace our modern roots and the star in the wall represents all the men of the O.S.S. who gave their lives in service to the nation. The book beneath that star lists their names.

Now look to the right. There are over 80 stars on that wall. More than one for every year of our existence. And those stars commemorate the men and women of this agency who gave their lives in service to our nation. There are analysts on that wall and those men and women walk through the same doors you just walked through and strode across the seal on which you now stand.

Now, there are many, many markers in many, many buildings in Washington commemorating many, many good men and women. But this building, this organization is different. We labor in the shadows, and even in death, many of our colleagues remain unknown, not only to the public, but to all save their families and a few fellow officers.

Your class starts in this place because you are linked to all those who have come before and all who will come after. The career analysts program is more about mission, values and culture than it is about skills. It’s about why we exist and the standards we hold ourselves to, and that you will be expected to hold yourself to.

You’ve joined a very select group of men and women, and in the weeks ahead you will come to appreciate how unique that group is.’

At that point, Michael, I hold up a copy of the President’s Daily Brief.

‘This is what the building is all about. It does not look like much. The first few times you read it, you may not be impressed. It looks simple, and it is, if we do it right.

But everything here, the case officers in the field, the analysts at the desk, the support people, the clerical people, the collection gadgets, are all geared to produce this slim document six days a week, 52 weeks a year for the most important and powerful person in the world, and for a handful of close advisers.

The DI mission — your mission — is to make the complex intelligible. Not simple; intelligible. To make our guy smarter than their guy, whether it’s across a mahogany conference table or across a battlefield. And you’re going to do that by explaining in this document and others the forces at work on this issue, the other fellow’s perspective, and the risks and opportunities in it for the United States.

Now, one of the people I worked with when I started used to say that if he could do anything for a new intelligence officer would be to take them to Nevada, see an A-bomb test. Not me. I would take you to Honolulu, where I went to grad school. We’d get lunch at a little seaside café I knew. And while you’re munching your teriyaki burger, I have you face the water. And I tell you to look to your right at that notch in the mountains. That’s Kolekole Pass. And on December 7th, 1941, Japanese Zeros streamed through that pass, passed in front of where you are now, and attacked on on your left, where the Arizona Memorial now sits in which to this day gives up pieces of sailors and marines still trapped inside. And I would tell you that that is what happens to a nation that has all the pieces of the puzzle but does not have a Directorate of Intelligence to put them together.

Now, sadly, sadly, after September 11th, I’d have to take you to another island, to Ground Zero at the tip of Manhattan for a different lesson. Someday, God forbid, your very best may not be good enough. And if that happens, you have to steel yourself. Critique your performance. Draw the right lessons. Rededicate yourself to the mission even as the waves of criticism that, merited and unmerited, break over you. We do not have the option of quitting our post or walking away or answering back.

We serve in silence.

Now, I believe that there are those in the world who would do us harm, take our liberty or livelihood, imperil our children and our families. We are on guard. All of us, as much as the cop on the beat or the soldiers at their post. Only we stand in the dark places in the world, places where the United States does not want to be seen, where people the United States does not want to be seen with hold power.

The Central Intelligence Agency is the eyes and ears of the nation and the Directorate of Intelligence is the voice of the CIA.

I believe knowledge is power, that good policy is rooted in superior knowledge. I believe that this agency is often the critical source of that knowledge. And I also believe that the United States is a force for good in the world. But how effective we are depends as much on our knowledge as it does on our raw power and intentions.

What we do, what you will be expected to do is terribly difficult and terribly important. That was true in 1766 when Washington wrote, ‘There’s nothing more necessary than good intelligence to frustrated designing enemy. And nothing requires greater pains to obtain.’

And it is, if anything, truer today because the enemies are more designing — to use Washington’s term — and even more powerful. When we get it wrong, American lives can be lost. If we are right, but ineffective in getting our message across, the consequences could be the same as getting it wrong.

The language of business is much in vogue. But we’re not a business. We’re a profession, a profession that you now join. A profession with its own ethics and standards. Part of it is DI tradecraft, about which you’ll hear much and learn much. But it’s more than that.

We are a secret intelligence organization in a democracy and we often work the gray areas. An organization chartered by our government to break the laws of other governments. And this puts a heavy obligation on us to be honest and ethical in all our dealings — with one another, with the consumers of our services, and with the people of the United States. DI culture emphasizes respect for ideas and people and for expertise at all levels, in all the professions represented in our directorate. And all of us have a shared responsibility in maintaining DI tradecraft and standards.

The demands on us are great. Hours can be long. Flexibility is essential to success here. And there’s a sense of service and sacrifice and patriotism – although it’s not talked about much.

There will be late dinners and missed events in the course of your career. There will be times when it could be hard to read a newspaper or watch the news, perhaps because what they have to say is incorrect; sometimes because what they have to say is too true. These things will take a toll on you, and on your family.

But there are rewards, too. And none greater than the knowledge that what you do matters. The work is important. You will make a difference. I’ve seen it time and time again over the course of my career. Time and time again, the men and women this building have pointed the way. And in so doing, made the world a little better, a little safer.

So, as you go through your career, I hope you’ll recall standing in this room on this day. I hope you come to appreciate the spirit of service and sacrifice and patriotism that imbues this antechamber and is exercised in the belief captured on the wall behind you — that one pillar of our democracy is a commitment to truth.

Take a moment. Look around. With new eyes.

That’s it, Michael.

MICHAEL MORELL: Marty… I just have two things to say. One is I have tears in my eyes at this moment.

And two, it’s now obvious not only why you were my mentor, but why you rose to be the number three at the Central Intelligence Agency. Marty, thank you so much for joining us today to tell us the Tiananmen story and to to share that inspirational speech that you gave so many times. Thank you so much.

MARTIN PETERSEN: Thank you, Michael.