There was a time when European governments couldn’t utter a fiscal policy statement without mentioning the word “austerity.” Now, the concept seems to have all but disappeared from public discourse.

Is the era of austerity finally over, and did austerity policies — essentially, those encompassing spending cuts and tax increases — achieve what they were supposed to achieve?

Those were the words of U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May when she spoke to her Conservative Party delegates at its annual conference in early October. Speaking to the embers of a party that had itself introduced an austerity program eight years previously, May said: “A decade after the financial crash people need to know that the austerity it led to is over.”

Britain’s austerity program saw dramatic cuts to welfare spending and public services and tax increases introduced in the hope of reducing the U.K.’s budget deficit (where spending outweighs revenues). The measures hit local councils hard (which are allocated funding from the government) with many reporting funding gaps.

Ten years on from the financial crisis and austerity measures seemed to have died on the continent too as a wave of populist politics has swept through Europe, turning much of the public against their established political parties and their unpopular programs.

Portugal, Spain, Greece and Italy — arguably those hit the most by the sovereign debt crisis — have all been relaxing their economic policies.

In Lisbon, the 2015 general election led to a socialist government that campaigned on ending austerity. The minimum wage has been increased every year since the appointment of this government and it’s set to break the 600 euros ($688) per month threshold next year. The same salary was 485 euros back in 2014.

Spain’s latest budget plan also intends to raise the minimum wage by 22 percent, the biggest increase in 40 years, according to newspaper El Pais.

In Rome, the anti-establishment government has challenged the EU with measures that will increase public spending and fulfil its biggest campaign pledges.

In Greece, the government was until August forced to implement policies dictated by its creditors. Now that the country is no longer subject to a bailout program, Athens is also looking to show that austerity is over, mainly ahead of a General Election next year.

Growing at a respectable (if not remarkable) 2.1 percent in the second quarter of 2018, year-on-year, Europe is looking much better economically than it did a decade ago, and governments are spending accordingly.

“We’ve moved into a clear recovery phase and government finances are on a much firmer footing,” Paul Donovan, a chief economist at UBS Global Wealth Management, told CNBC in October.

“That’s not necessarily the result of tightening the belt and austerity measures, but recent better growth means that governments are not so fiscally pressured. It’s part of a natural cyclical story which gives politicians room to play around a little more, and we move into an era with more fiscal options. So austerity is sort of over,” he said.

Traditionally, resistance to unbridled spending has come from Germany although any relaxation of budget restraint there could come about more by accident than design when Chancellor Angela Merkel leaves office – expected in 2021, if not before.

Austerity, for good or bad, will be one of Merkel’s legacies whether she likes it or not, and the country’s insistence on spending restraint has drawn criticism far and wide. France’s President Emmanuel Macron even accused Germany of having a “budget fetish” earlier this year, not most people’s idea of fun.

But Macron is not the first to criticize Germany’s apparent obsession with what it would see as fiscal prudence and there is an increasing amount of Germans, businesses included, that say Germany’s trade surplus is “toxic” and more needs to be spent on domestic infrastructure.

With Merkel’s departure from politics, Germany, the erstwhile guardian of austerity in Europe, could be a much weaker advocate for spending restraint.

Berlin is proud of its budget surplus and is unlikely to change policies dramatically any time soon, but if it did, this would amount to a sea change for Europe.

Many Germans felt that austerity measures were a necessary tonic for southern euro zone states that they believed had mismanaged their finances (such as Merkel’s former Finance Minister Wolfgang Schauble — nicknamed the “architect of austerity” — who repeatedly told Greece not to blame others for its financial problems). While others, like the former center-left Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel, argued that austerity measures were driving the EU toward the brink of collapse.

Now, facing a populist backlash in Germany and beyond, and policy differences within her own fractious coalition, Merkel has to decide whether to maintain her support of austerity — one that could have caused a populist surge — or gently abandon it. Germany’s Finance Ministry was not available for comment when contacted by CNBC.

“Austerity stopped for better or worse. In some cases, such as Germany, the fiscal stimulus owes to exceptionally benign fiscal circumstances. In other cases, such as those of Italy, the turn away from post-crisis prudence, that started already in 2016 and is now exacerbated by the pricey spending plans of the radical government, is premature,” Florian Hense, economist at Berenberg, told CNBC via email.

One major — and perhaps, last — bastion of fiscal discipline is the European Commission.

The executive arm of the EU, that signs off on euro zone budgets, has powers allowing it to “punish” member states that break the rules over their budgets (essentially, their spending plans should not see spending exceed 3 percent of gross domestic product) and countries are meant to work toward reducing their debt — the official debt ceiling is 60 percent of GDP. The reality is often very different, however.

Most of the major economies in Europe are exceeding official debt limits. Even Germany had a debt-to-GDP ratio of 61.5 percent in the second quarter of 2018, the latest statistics from Eurostat show. France has a debt pile equal to 99.1 percent and Italy’s debt ratio stands at 133.1 percent.

Part of the problem of increasing spending is that it only adds to countries’ debt piles, making them vulnerable to future shocks and potential defaults. In Europe too, some countries are more vulnerable than others, economists warn.

“We’re evolving,” Paul Donovan from UBS noted, “we’re in a cyclical environment where governments have more room to act but debt-to-GDP ratios still have to come down and different economies in Europe are moving at different speeds.”

The lack of sanctions by the Commission has done nothing to bolster its credibility and might have emboldened some governments to feel like it was better to appease and support discontented voters rather than an unpopular bureaucratic institution in Brussels.

One government that seems to be in outright rebel mode right now is Italy. An inconclusive election in March earlier this year saw Italy’s old guard of politicians jettisoned in favor of two upstart, populist parties who promised to throw the austerity rulebook out of the window.

Having formed a euroskeptic coalition, the right-wing Lega party and anti-establishment Five Star Movement (M5S) has proposed spending plans for 2019 that look to reverse unpopular austerity measures and reforms as well as more “shock” proposals like introducing a guaranteed basic income. Italy says the budget will see it hit a deficit of 2.4 percent of GDP in 2019, above a previously agreed target of 0.8 percent.

Needless to say, the Commission is irate and has rejected the plans. But Italy’s coalition have so far appeared unrepentant, with Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini (the head of the Lega party) threatening to overturn the EU’s “imposed” policies, prompting a showdown with Brussels.

“We’re seeing electoral promises trying to capitalize on that sense of inequality and lack of wage growth,” Alberto Gallo from Algebris Investments noted.

“But in practice, many of these policies are just quick fixes that don’t work in the medium term. In fact, they can create more problems, more debt and more inflation. It works a lot more to invest in productivity through education, infrastructure and research, but politicians are not inclined to do reforms, they try to sell revolutions.”

Gallo said there was something of a “selective hearing” approach in Germany and the Commission regarding austerity, however. “I wouldn’t proclaim the end of austerity in Europe, we’re still a long way from that. France and Italy are pushing for more spending and a stronger fiscal union, but Germany and the European Commission appear to have deaf ears.”

It’s not hard to see why voters across Europe are fed up with cuts but it’s important to remember how we got to the point where “austerity” became a buzzword for European finance ministers.

Euro zone members Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Cyprus all experienced sovereign debt crises to varying degrees and for various reasons from 2009 onwards.

These ranged from the popping of property bubbles (Ireland and Spain, for example) to the major failing of sectors like tourism and shipping that had been affected by the global financial crisis, as well as the general mismanagement of government budgets and the accrual of large amounts of debt, like we saw in Greece.

Controversially nicknamed the “PIGS” (meaning Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain, the acronym omitting Cyprus and sometimes including Italy), bailed-out nations were given financial lifelines by the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and the European Commission, a trio of lenders that became known as the “troika.” Those lifelines came at a price, however.

While the causes of their financial misfortunes might have differed, the bailout nations shared in common the lenders’ insistence that they adhere to strict fiscal austerity measures in return for financial aid. The main aim of this was to get countries to reduce budget deficits, debt piles and, essentially, the danger they posed to the euro zone’s financial stability.

It wasn’t just bailed-out nations that were press-ganged into implementing cost-cutting measures. The austerity drive spread throughout Europe to countries that were experiencing recessions after the financial crisis and the U.K., Italy, France and even Germany introduced fiscal austerity programs in 2010 and 2011. Soon enough, austerity measures were de rigueur in Europe.

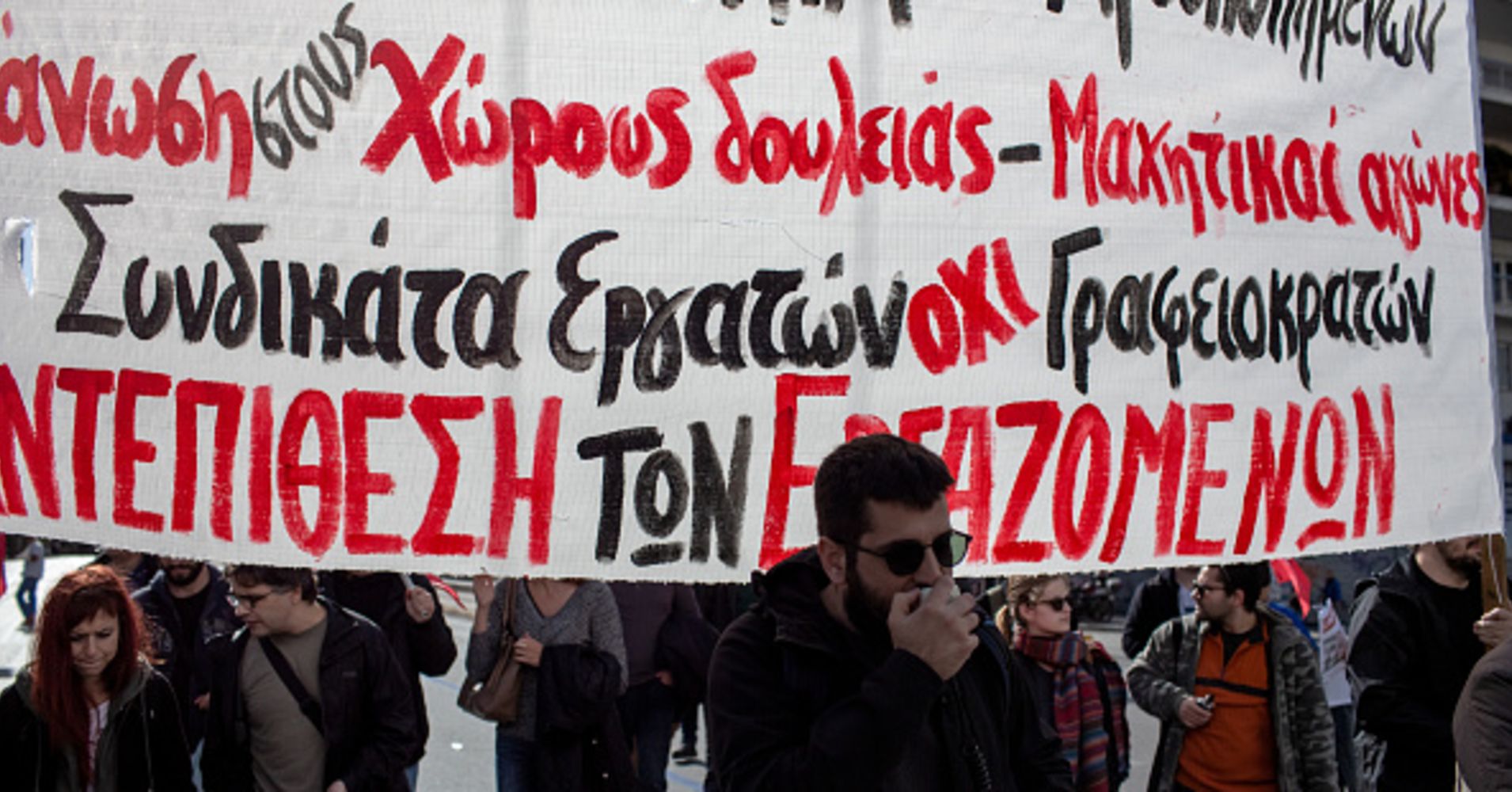

Of course, with the public largely bearing the brunt of austerity measures, it’s not surprising that cost-cutting policies were not welcomed. Anti-austerity protests were common across Europe and there was often violence between protesters and the police. Anti-austerity parties and politicians were popular (remember then-French President Francois Hollande’s pledge to introduce a 75 percent tax on incomes over 1 million euros?) and even came to power.

Although Greece’s left-wing party Syriza promised, and held, a referendum in which a majority of the public voted against accepting another bailout, anti-austerity ideologies were quickly faced with brutal realities.

With Greece’s place in the euro zone hanging in the balance, basic commodities running low in stores and the country looking like it might default on its debt — a potentially cataclysmic scenario for Europe — in the end the public’s “no” vote was ignored and a third bailout was accepted.

Fast forward to 2018, and like its euro zone neighbors, Greece finally exited its bailout. But it’s not unscathed and now bears the indelible mark of debt — as do its neighbors. At 179.7 percent of GDP, Greece has the second-highest debt pile in the world after Japan.

“So, it is not just words, but actions, even though it may just sound as empty words to those that are not back to where they were before the double whammy of the financial and euro crisis hit the euro zone — think those that have lost their jobs or the lower income quartiles that have seen their wages grow only very slowly,” Hense from Berenberg told CNBC. reads odd

Economists and investors worry about Europe’s debt profile and a lack of fiscal policy in the euro zone.

“Europe is at a crossroads. It needs to make a decision whether it wants closer union and closer fiscal policy. At the moment they have a common currency but not a common fiscal policy,” Gallo said, adding that “the problem of austerity intersects structural imbalances which are at the heart of the euro zone” such as the lack of a common fiscal policy.

“All countries benefit from being in the euro zone but some benefit more than others. The low euro benefits the likes of France and Germany whereas the common market allows for economies of scale for everyone,” he added.

Others warn that Europe needs to “fix the roof while the sun is shining” (to quote former U.K. Finance Minister George Osborne) especially when the region is continuing to enjoy the last gasp of low interest rates thanks to the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing program, expected to finish at the end of this year.

There are concerns European governments, keen to move away from austerity, unpopular reforms, placate voters and stay in office, are not heeding that warning.

“Most European governments are trying to push higher spending and larger fiscal imbalances thinking that the current environment of low rates and high complacency will last forever,” Daniel Lacalle, chief economist at Tressis Gestion, told CNBC via email.

“The euro zone countries have saved more than one trillion euros in interest expenses due to the ECB quantitative easing but they have spent it all. The end of austerity happened a few years ago, and what we are seeing is that almost all euro zone countries are spending above the 2007 levels, so raising spending further is the recipe for another debt crisis in the near future.”